Until a few months ago, the complaint that Canada’s economy isn’t diverse enough, and is too reliant on energy exports, seemed to be a purely academic matter.

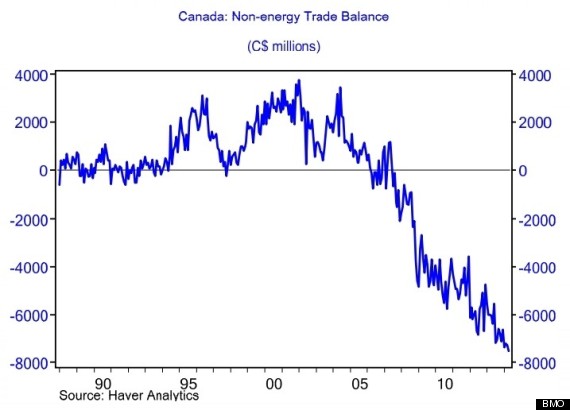

When economists warned, for example, that Canada is running an enormous deficit in non-energy trade (i.e. we just aren’t making and selling much other than energy), a common response would be, “So what? In a global economy, we don’t need to produce everything we consume, do we?”

That certainly was the attitude of our federal government which (until very recently) saw little reason to prop up central Canada’s struggling manufacturing sector, and focused much of its efforts on convincing the U.S. to build a pipeline for Canadian oil.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

But a massive slide in oil prices has a surprisingly rapid effect on people’s perspectives. In what appears to be a change of heart, Stephen Harper’s cabinet spent much of the last week announcing subsidies for manufacturers.

They may be getting a little alarmed by what the economic data is showing. Until recently the experts were telling us that we need not worry too much about a slide in oil prices, because the loonie would fall with it, making Canadian exports cheaper and boosting manufacturing. Thus with rose-coloured glasses planted firmly on their faces, they sat back and waited for the “great rotation” to a manufacturing-led economic expansion.

Well guess what? It’s not happening. Canada has recorded large trade deficits in recent months, and those deficits aren’t just the result of oil exports going for less.

Exports of industrial machinery and consumer products fell 3.5 per cent in the latest numbers from StatsCan, despite the loonie having fallen 10 cents U.S. in little more than a year. Manufacturers continued to shed employees, with 11,500 fewer manufacturing jobs at the end of 2014 than there were a year earlier.

So why is the falling loonie not helping? Thanks to years of this we-don’t-need-factories attitude, we don’t actually have much manufacturing anymore. Or at least not enough to do much good, now that the loonie is falling.

A report from CIBC World Markets, issued this week, argues that so much Canadian manufacturing capacity was destroyed in the past decade that we just aren’t producing enough for manufacturers to take over where oil exporters left off.

“Across the full spectrum of manufacturing, available capacity has melted away in the past decade,” the CIBC economists wrote.

Simply put, there’s no one around to take advantage of our now-cheaper exports.

Story continues below

The report noted that from 2002 to 2012, as the Canadian dollar steadily grew in value, the country lost about a quarter of all its manufacturing businesses.

A strong loonie propelled by then-high oil prices did its part to discourage manufacturing in Canada. CIBC notes that the sectors that are most sensitive to changes in the dollar’s value lost 12 per cent of their manufacturing capacity over the past decade.

But it wasn’t just currency speculators who eroded Canadian manufacturing; investors played a part as well. Just look at where capital is going in Canada’s economy. Energy accounted for 27 per cent of all public and private investment in 2013, despite accounting for less than 10 per cent of Canada’s GDP, and only 1.6 per cent of total employment.

Manufacturing, on the other hand got less than five per cent of all investment, despite accounting for 10 per cent of GDP and 11 per cent of all jobs.

It is, in part, a question of attitudes and expectations, and right now nobody expects Canada to manufacture. Even with labour costs some 10 per cent cheaper in Canada relative to the U.S. than they were a year ago, Ford still recently chose Mexico over Ontario for a factory.

And so the job market continues to sputter.

Fortunately, Canada’s over-reliance on energy isn't a permanent condition. It will take some time to fix — time for investors and currency speculators and everyone else to realize that this economy doesn’t have to be a one-trick pony.

“We will need to sustain an 80-85 cent Canadian dollar for several years to come for all of the benefits to show through in our

factory sector,” CIBC concluded.

That exchange rate would probably mean oil prices would also have to stay down for some time. Painful as that may be to the oil-rich provinces, it may prove to be good news in the long run, if it means a more diverse, more resilient economy.

When economists warned, for example, that Canada is running an enormous deficit in non-energy trade (i.e. we just aren’t making and selling much other than energy), a common response would be, “So what? In a global economy, we don’t need to produce everything we consume, do we?”

That certainly was the attitude of our federal government which (until very recently) saw little reason to prop up central Canada’s struggling manufacturing sector, and focused much of its efforts on convincing the U.S. to build a pipeline for Canadian oil.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

But a massive slide in oil prices has a surprisingly rapid effect on people’s perspectives. In what appears to be a change of heart, Stephen Harper’s cabinet spent much of the last week announcing subsidies for manufacturers.

They may be getting a little alarmed by what the economic data is showing. Until recently the experts were telling us that we need not worry too much about a slide in oil prices, because the loonie would fall with it, making Canadian exports cheaper and boosting manufacturing. Thus with rose-coloured glasses planted firmly on their faces, they sat back and waited for the “great rotation” to a manufacturing-led economic expansion.

Well guess what? It’s not happening. Canada has recorded large trade deficits in recent months, and those deficits aren’t just the result of oil exports going for less.

Exports of industrial machinery and consumer products fell 3.5 per cent in the latest numbers from StatsCan, despite the loonie having fallen 10 cents U.S. in little more than a year. Manufacturers continued to shed employees, with 11,500 fewer manufacturing jobs at the end of 2014 than there were a year earlier.

So why is the falling loonie not helping? Thanks to years of this we-don’t-need-factories attitude, we don’t actually have much manufacturing anymore. Or at least not enough to do much good, now that the loonie is falling.

A report from CIBC World Markets, issued this week, argues that so much Canadian manufacturing capacity was destroyed in the past decade that we just aren’t producing enough for manufacturers to take over where oil exporters left off.

“Across the full spectrum of manufacturing, available capacity has melted away in the past decade,” the CIBC economists wrote.

Simply put, there’s no one around to take advantage of our now-cheaper exports.

Story continues below

The report noted that from 2002 to 2012, as the Canadian dollar steadily grew in value, the country lost about a quarter of all its manufacturing businesses.

A strong loonie propelled by then-high oil prices did its part to discourage manufacturing in Canada. CIBC notes that the sectors that are most sensitive to changes in the dollar’s value lost 12 per cent of their manufacturing capacity over the past decade.

But it wasn’t just currency speculators who eroded Canadian manufacturing; investors played a part as well. Just look at where capital is going in Canada’s economy. Energy accounted for 27 per cent of all public and private investment in 2013, despite accounting for less than 10 per cent of Canada’s GDP, and only 1.6 per cent of total employment.

Manufacturing, on the other hand got less than five per cent of all investment, despite accounting for 10 per cent of GDP and 11 per cent of all jobs.

It is, in part, a question of attitudes and expectations, and right now nobody expects Canada to manufacture. Even with labour costs some 10 per cent cheaper in Canada relative to the U.S. than they were a year ago, Ford still recently chose Mexico over Ontario for a factory.

And so the job market continues to sputter.

Fortunately, Canada’s over-reliance on energy isn't a permanent condition. It will take some time to fix — time for investors and currency speculators and everyone else to realize that this economy doesn’t have to be a one-trick pony.

“We will need to sustain an 80-85 cent Canadian dollar for several years to come for all of the benefits to show through in our

factory sector,” CIBC concluded.

That exchange rate would probably mean oil prices would also have to stay down for some time. Painful as that may be to the oil-rich provinces, it may prove to be good news in the long run, if it means a more diverse, more resilient economy.