Arts graduates spend years dissecting texts like "Waiting for Godot."

And like the characters in Samuel Beckett's absurdist play, generations of them have been stuck in one place, unable to find jobs for which their degrees might qualify them.

That's the conclusion of a Statistics Canada study released on Wednesday that found the number of graduates working in jobs they're overqualified for hasn't changed much from 1991 to 2011.

It found that among university graduates aged 25 to 34 years old, 18 per cent of them were in jobs that required a high school education or less, a statistic that changed little in those two decades.

But one of its most notable findings was that about one-third (~32 per cent) of humanities graduates (people who studied history, literature and philosophy) were working jobs that would require a high school education or less in 2011.

That was more than people who had studied social sciences and law, and graduates of visual and performing arts programs.

Meanwhile, fewer than 10 per cent of education graduates had jobs that typically required a high school degree, and graduates in fields such as health, architecture and engineering also had rates below 15 per cent.

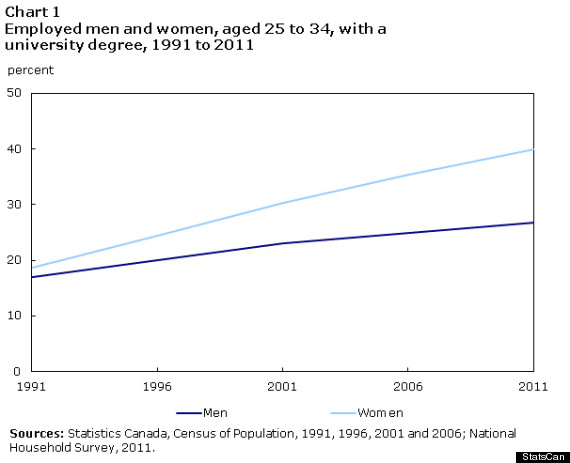

The numbers came as more workers between the ages of 25 and 34 obtained university degrees between 1991 and 2011.

![overqualified]()

The statistics told a familiar story for Eric Skoff, who finished school with two humanities degrees two years ago and is still struggling to find a full-time job, Global News reported.

In that time, he has worked as a barista and ran an after-school programs, both jobs for which he's overqualified.

While the number of overqualified workers between 25 and 34 hasn't changed, Skoff believes the number of humanities grads unable to find work is new to Generation Y.

"I think this has been the first generation where the younger generation is not going to be as successful as their parents," he told the network.

While several humanities graduates are finding themselves overqualified for their jobs, that doesn't necessarily mean they make up the bulk of Canada's overqualified workforce.

In fact, when you look the distribution of overqualified workers across fields of study, they're not even the highest.

Among overqualified males working jobs that require a high school education, 25.8 per cent were business graduates, while 21.5 per cent came from social sciences and law, and 14.1 per cent had studied humanities.

Meanwhile, 25.7 per cent of overqualified women had graduated from social and behavioural sciences and law, 20.9 per cent came from business and 15.1 per cent graduated in humanities.

StatsCan analysts also came up with a probability score to determine which factor most affected overqualification.

They found that immigrants with a degree obtained outside Canada or the U.S. were most likely to work jobs for which they were overqualified, and that only required a high school degree or less.

Humanities graduates had the next highest score, followed by visual and performing arts grads, and then students of social sciences and law.

And like the characters in Samuel Beckett's absurdist play, generations of them have been stuck in one place, unable to find jobs for which their degrees might qualify them.

That's the conclusion of a Statistics Canada study released on Wednesday that found the number of graduates working in jobs they're overqualified for hasn't changed much from 1991 to 2011.

It found that among university graduates aged 25 to 34 years old, 18 per cent of them were in jobs that required a high school education or less, a statistic that changed little in those two decades.

But one of its most notable findings was that about one-third (~32 per cent) of humanities graduates (people who studied history, literature and philosophy) were working jobs that would require a high school education or less in 2011.

That was more than people who had studied social sciences and law, and graduates of visual and performing arts programs.

Meanwhile, fewer than 10 per cent of education graduates had jobs that typically required a high school degree, and graduates in fields such as health, architecture and engineering also had rates below 15 per cent.

The numbers came as more workers between the ages of 25 and 34 obtained university degrees between 1991 and 2011.

The statistics told a familiar story for Eric Skoff, who finished school with two humanities degrees two years ago and is still struggling to find a full-time job, Global News reported.

In that time, he has worked as a barista and ran an after-school programs, both jobs for which he's overqualified.

While the number of overqualified workers between 25 and 34 hasn't changed, Skoff believes the number of humanities grads unable to find work is new to Generation Y.

"I think this has been the first generation where the younger generation is not going to be as successful as their parents," he told the network.

While several humanities graduates are finding themselves overqualified for their jobs, that doesn't necessarily mean they make up the bulk of Canada's overqualified workforce.

In fact, when you look the distribution of overqualified workers across fields of study, they're not even the highest.

Among overqualified males working jobs that require a high school education, 25.8 per cent were business graduates, while 21.5 per cent came from social sciences and law, and 14.1 per cent had studied humanities.

Meanwhile, 25.7 per cent of overqualified women had graduated from social and behavioural sciences and law, 20.9 per cent came from business and 15.1 per cent graduated in humanities.

StatsCan analysts also came up with a probability score to determine which factor most affected overqualification.

They found that immigrants with a degree obtained outside Canada or the U.S. were most likely to work jobs for which they were overqualified, and that only required a high school degree or less.

Humanities graduates had the next highest score, followed by visual and performing arts grads, and then students of social sciences and law.

Overqualification among recent university graduates in Canada.

Like this article? Follow our Facebook pageOr follow us on TwitterFollow @HuffPostCanada