It’s a trend seen in the U.S. in recent years, a sign of growing wealth inequality: The segmenting of the retail market away from middle class-oriented brands to low-end and luxury brands.

And according to a recent report from CIBC World Markets, Canada is experiencing its own version of the phenomenon today.

Economists Avery Shenfeld and Benjamin Tal say the biggest winners in Canadian retail these days are dollar stores, and they’re winning because wage gains are becoming increasingly unequal.

At the same time, Canada is about to have a boom in luxury retail space, as U.S. department stores Nordstrom and Saks set up shop north of the border, in some instances displacing some more middle-class department stores like Sears.

Shenfeld and Tal say it has to do with the fact that incomes at the upper end are growing faster than incomes at the lower end.

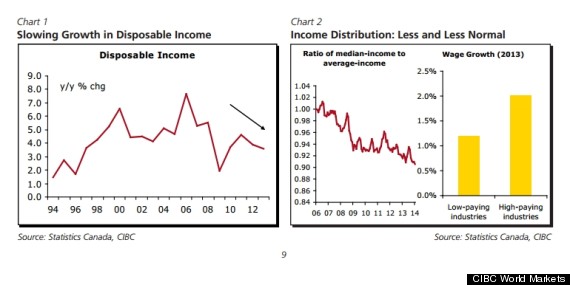

“Increasingly, whatever wage gains there are have been tilted to a select group of higher-paid sectors, leaving the median worker with leaner improvements,” they write.

“That extends a pattern going back more than a decade,” the authors note.

As the charts below show, wage growth in high-paying industries was about two per cent in 2013, while wage growth for lower-income workers was only one per cent. Growth in disposable income is on a long-term downward trend.

![cibc wage chart]()

Those meagre gains are putting pressure on Canadian consumers at the lower end of the income scale, and sending them to dollar stores. The CIBC report notes that disposable income grew 3.6 per cent last year, which was the slowest pace of growth outside a recession since 1996.

To an extent, this trend away from middle-class retail can be seen in recent earnings numbers. Low income-oriented Dollarama saw profits rise 20 per cent in the most recent quarter that wasn't impacted by the severe winter, while middle class oriented Target has been struggling to gain a foothold in Canada since opening last year, racking up a nearly $1-billion loss in the year it’s been operating.

But this pattern is also good news at the upper end of the income scale, Shenfeld and Tal say, because higher wage gains at the top mean more room for luxury retailers.

With Nordstrom and Saks headed for Canada, there’s an “upcoming boom in luxury store square footage,” the CIBC economists note.

But Canada hasn’t reached the levels of inequality seen in the states, and Canada’s one-percenters aren’t as rich as their American brethren, so those luxury retailers shouldn’t expect the kind of extravagant spending they see in the States, the CIBC economists say.

“As of 2010, a U.S. tax-filer had to earn $359,400 to be in the top one per cent of Americans. The corresponding figure for Canada was only $201,400,” they note.

Shenfeld and Tal still see the possibility of overall retail sales growth rising a percentage point to 4 per cent this year. But that’s not because Canadians will be buying more (they won’t), it’s because inflation will raise prices and sales numbers, they said.

And according to a recent report from CIBC World Markets, Canada is experiencing its own version of the phenomenon today.

Economists Avery Shenfeld and Benjamin Tal say the biggest winners in Canadian retail these days are dollar stores, and they’re winning because wage gains are becoming increasingly unequal.

At the same time, Canada is about to have a boom in luxury retail space, as U.S. department stores Nordstrom and Saks set up shop north of the border, in some instances displacing some more middle-class department stores like Sears.

Shenfeld and Tal say it has to do with the fact that incomes at the upper end are growing faster than incomes at the lower end.

“Increasingly, whatever wage gains there are have been tilted to a select group of higher-paid sectors, leaving the median worker with leaner improvements,” they write.

“That extends a pattern going back more than a decade,” the authors note.

As the charts below show, wage growth in high-paying industries was about two per cent in 2013, while wage growth for lower-income workers was only one per cent. Growth in disposable income is on a long-term downward trend.

Those meagre gains are putting pressure on Canadian consumers at the lower end of the income scale, and sending them to dollar stores. The CIBC report notes that disposable income grew 3.6 per cent last year, which was the slowest pace of growth outside a recession since 1996.

To an extent, this trend away from middle-class retail can be seen in recent earnings numbers. Low income-oriented Dollarama saw profits rise 20 per cent in the most recent quarter that wasn't impacted by the severe winter, while middle class oriented Target has been struggling to gain a foothold in Canada since opening last year, racking up a nearly $1-billion loss in the year it’s been operating.

But this pattern is also good news at the upper end of the income scale, Shenfeld and Tal say, because higher wage gains at the top mean more room for luxury retailers.

With Nordstrom and Saks headed for Canada, there’s an “upcoming boom in luxury store square footage,” the CIBC economists note.

But Canada hasn’t reached the levels of inequality seen in the states, and Canada’s one-percenters aren’t as rich as their American brethren, so those luxury retailers shouldn’t expect the kind of extravagant spending they see in the States, the CIBC economists say.

“As of 2010, a U.S. tax-filer had to earn $359,400 to be in the top one per cent of Americans. The corresponding figure for Canada was only $201,400,” they note.

Shenfeld and Tal still see the possibility of overall retail sales growth rising a percentage point to 4 per cent this year. But that’s not because Canadians will be buying more (they won’t), it’s because inflation will raise prices and sales numbers, they said.